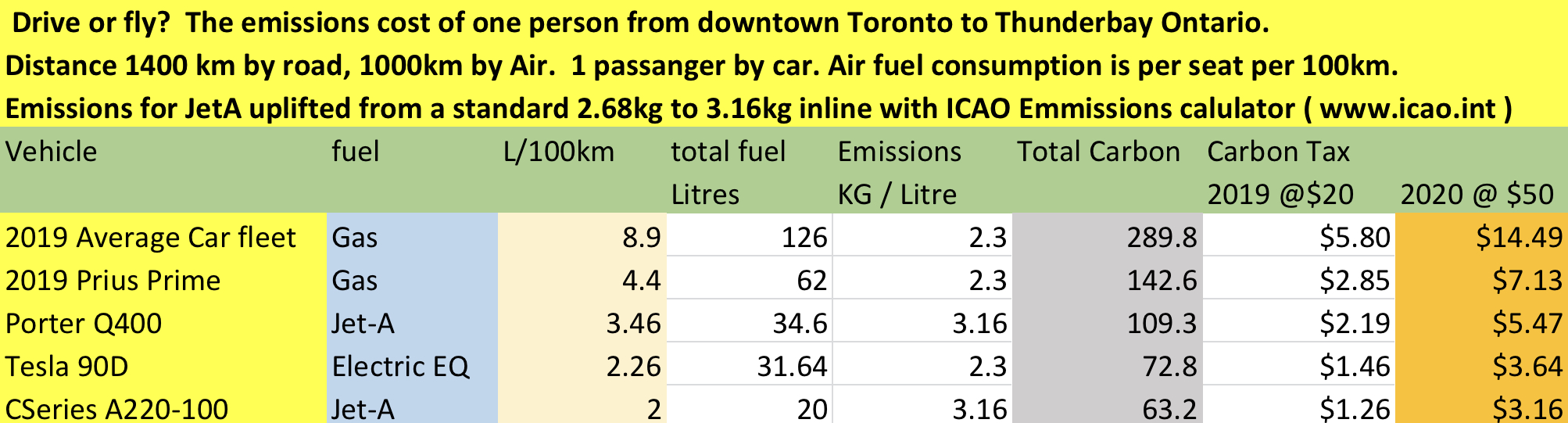

Canada is implementing its long-promised carbon tax on everything from natural gas to jet fuel. The goal of the carbon tax is to reduce emissions by encouraging Canadians to work, live and travel as efficiently as possible. Today the carbon tax is $20 per ton (4.4 cents per liter on car gasoline ) increasing to $50 per ton (11 cents per liter) by 2022.

It may take years to create meaningful change, and some results will surprise many of its supporters. One notable surprise is that Canada’s new carbon tax appears to encourage air travel rather than reduce it.

So how does a new tax on fuel (increasing the cost per liter on both jet fuel and car gasoline) favor traveling by air over driving to your destination? How can new aviation emissions created by the soaring demand for air travel, possibly help Canada meet its 2030 emissions targets? It turns out that advances in technology, engineering and material sciences have turned air travel into a shining symbol of efficiency that, per seat, has outpaced the automobile.

In the 1970s, iconic aircraft such as the Boeing 707 and the supersonic Concorde defined the dawn of the jet age. Fast, extremely expensive and noisy, the Concorde was the pinnacle jet of its era. Guzzling up to 17 liters per 100 km per seat, leaving a visible exhaust trail, it noisily rocketed the wealthy “jet set” to their destinations. Fifty years later this mindset still lingers. Ask almost anyone outside the aviation industry which method of transportation burns less gas or has a lower carbon footprint per km, flying or driving, they will say driving. For years this was the right answer, but not anymore.

Today’s jet aircraft could not be more different than its gas guzzler ancestor. A new C-Series jet or an Airbus A319neo burns 1/9th the gas of the old Concorde, as little as 1.93 liters per 100 km per seat. This beats even the best traveling salesman’s Toyota Prius Prime (now 4.4 liters per 100 km on the highway). Better yet, jets go in a straight line without the need for expanding expensive and environmentally unfriendly highways or the need to meander around towns, lakes and hills.

On the old overseas Concorde routes, the Boeing 787 Dreamliner can average 2.7 Liters per 100 km per seat. This fuel efficiency has enabled the cost of air travel to plummet, often beating the cost of a train or bus ticket. This is the main reason that there is no longer train or bus service to many Canadian cities. For an average citizen, there are now two common methods of domestic travel — drive a car or take a plane.

As air travel has taken off in popularity, the press is full of clichéd articles warning of the growing carbon emissions of jet travel, even going so far as to call aviation the “new coal”. In absolute terms aviation emissions continue to grow, up as much as 65% since 2005. Air travel in Canada has more than doubled in volume in the last 15 years and is expected to continue to soar. In Canada it has supplanted all other forms of interprovincial travel.

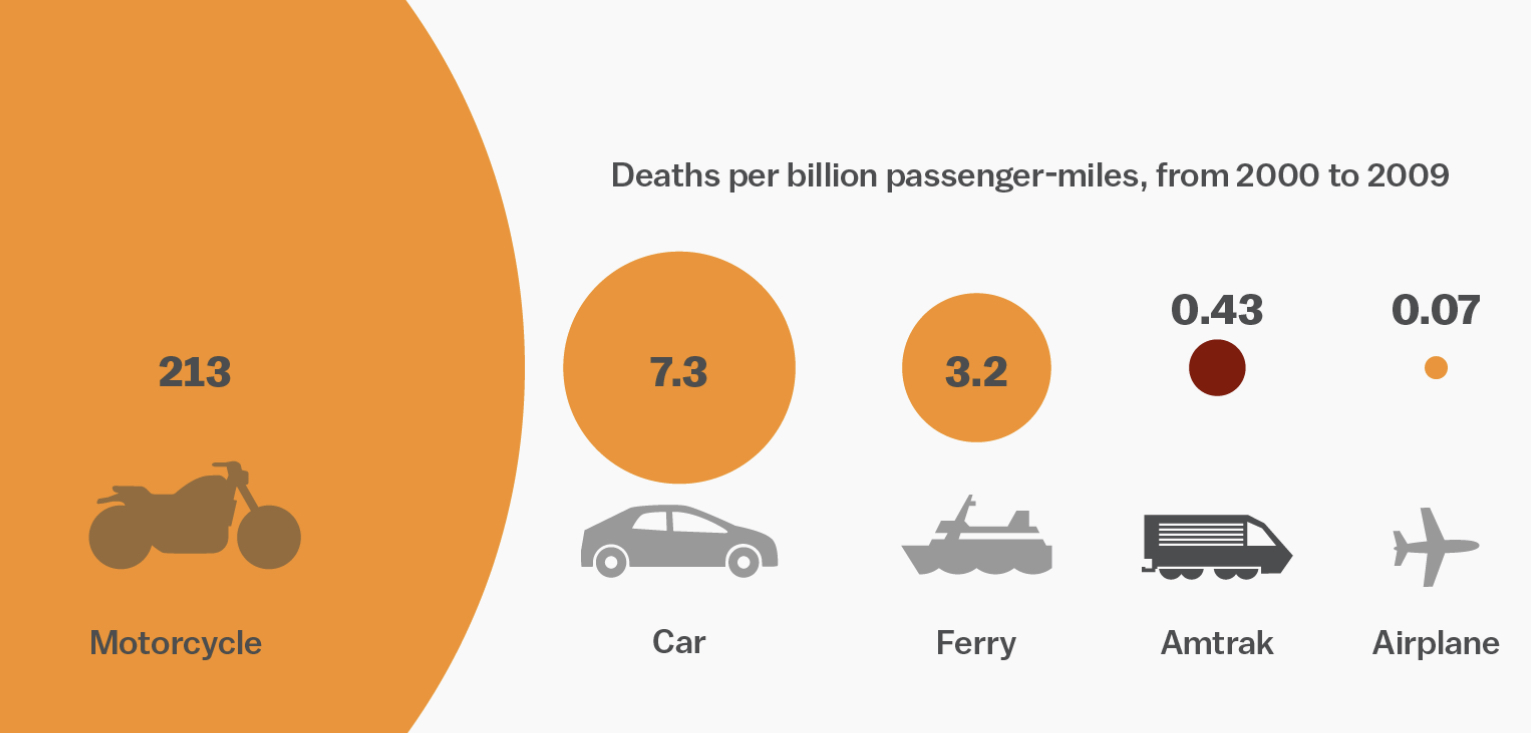

As airlines continue to adopt more fuel efficient technology, costs will keep dropping and people will continue the switch from road to air travel, reducing their individual emissions. This is the goal of the carbon tax. By reducing long-distance road trips, air travel is saving fuel and also taking the pressure off the need to pave over tens of thousands of acres of farmland and wilderness with new roads that would otherwise be required to handle Canada’s growing population. Turns out that the carbon tax has it right, soaring air travel is a good thing for our environment. It is also a lot safer and faster.

But there is a catch. While air travel has taken some of the pressure off the need to buildout our road network, we do need more aviation infrastructure. One airport in particular, Toronto Pearson which handles 30% of all Canadian passenger traffic, is straining under the load. It now has one of the worst overall on-time performance records of any major airport in North America. Long taxi times, missed connections, in-air holds and flow control are eating away at the emissions advantages of air travel out of Pearson.

The solution, if the Canadian government can see past the status quo, is a new jet airport just east of Toronto in Pickering. The new airport will also provide local jobs, reduce emissions indirectly by reducing commute times and reduce road congestion around Pearson.

Two kilometers of road will let you drive two kilometers. A two-kilometer-long runway connects Toronto to every community in Canada and the world. Spread the word — fly, don’t drive! Help reduce our carbon emissions by supporting new airport infrastructure!

Cross reference Sources:

? you’re so out of date it’s amusing, almost .

The emissions numbers are current and validated. It’s time to undo old thinking and the need for simple symbols. Surprise, building Pickering Airport will help us reduce carbon emissions. It’s the Infrastructure Paradox. Air traffic is not going away, but by decongesting Pearson we can reduce fuel burn and emissions